Almaysh Haidar Rizqullah

Hacettepe Üniversitesi

almaysh.rizqullah@hacettepe.edu.tr

LoveLive! School idol project series, simply called LoveLive! (ラブライブ!), is a Japanese multimedia project about a group of high school girls becoming “school idols” (description in the next figure) with original story by YATATE Hajime (矢立 肇)1 and original concept by KIMINO Sakurako (公野 櫻子)1 (PROJECT LoveLive!, 2013a;プロジェクトラブライブ!, 2013a). The project debuted on June 30th 2010 co-produced by Kadokawa through ASCII Media Works’ Dengeki G’s Magazine, Bandai Namco Music Live through the music label Lantis, and the animation studio Sunrise (Loo, 2010; Love Live! | Love Live! Wikia | Fandom, 2013). With the original tagline “The story which we make our dreams come true,” it has been produced through a variety of media, such as card games, periodicals, comics, TV anime, CDs with music and anime trailer videos, and mobile phone applications. It has also been developed through radio shows, live video streams, and through live concerts and events (Love Live! – Wikipedia, 2021; PROJECT LoveLive!, 2013b).

LoveLive! is arguably one of the most successful multimedia idol franchises in the history of modern Japanese pop culture, on par with the more established THE iDOLM@STER, followed by newer franchises like BanG Dream! and Umamusume Project. According to market research firm Hakuhodo, its highest yearly content revenue was ¥42.3 billion ($399 million) in 2015 (Hakuhodo Inc., 2015). Additionally, it placed first among Japan’s best-selling physical media franchises in 2016 earning ¥8.048 billion (out of ¥ 43.9 billion or $363 million in annual content income) (Loo, 2016). Celebrating its 15th anniversary this year, LoveLive! has given rise to six generations of school idol groups as well as two unique projects featuring a variety of characters and gimmicks that have been well welcomed and supported by fans (also called LoveLivers) both in Japan and abroad (プロジェクトラブライブ!, 2013b).

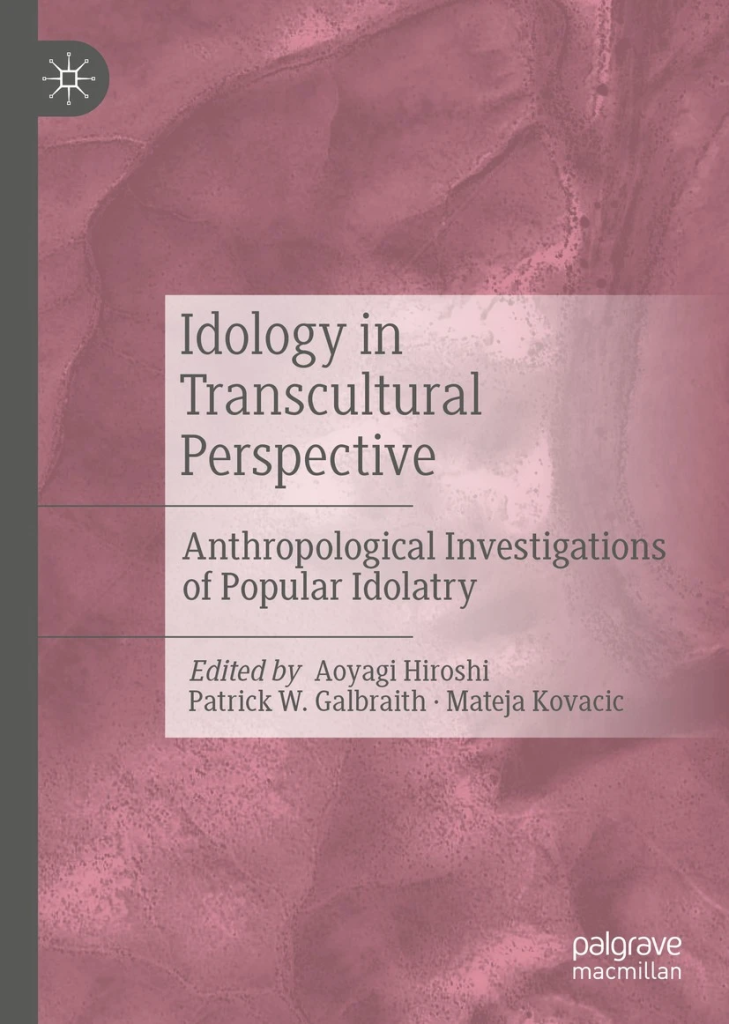

With this kind of popularity, LoveLive! is genuinely very interesting for someone researching idol culture in Japan; that includes KAWAMURA Satofumi (川村 覚文)1, who is a contributor in a 2022 book titled Idology in Transcultural Perspective: Anthropological Investigations of Popular Idolatry (Hiroshi et al., 2021). At the time, he was a junior associate professor at Kanto Gakuin University. In the book, he wrote the tenth chapter titled Love Live! as an Affective-Religious Medium in the Postsecular Era (Kawamura, 2021), which I will summarize first then review it with my perspective as both a LoveLiver since 2014 and as an aspiring academician.

In this tenth chapter, Kawamura divided it into five sub-chapter: Introduction, Postsecular and Capitalist Realism, The Technological Condition of Anime and Affect, The Voice of a Character and the Affective Interaction, and Conclusion. In addition to defining LoveLive!, he explained in the first sub-chapter why he saw the LoveLive! series as a religious and affective media in the postsecular age, equating the two properties. Using the idea that we live in a postsecular age, he said that values from digital media technology had replaced transcendental principles from religion. He claimed that although religion is the principle that permits the creation of both individuality and collectivity/trans-individuality, affect is essential to the emergence, which is why he associated religious with affective. He looked for the possibilities for LoveLivers to create an affective-religious collectivity through their affective experience of consuming the LoveLive! franchise in order to resist the postsecular technology governmentality. Kawamura only focused on the first two school idol groups in the series, μ’s and Aqours.

The second sub-chapter, Postsecular and Capitalist Realism, is basically four pages of Kawamura presenting definitions and other experts’ opinions regarding postsecularism, religion, and capitalist realism. Honestly, it feels like a waste of time reading all of these paragraphs except for the last one on page 245, just before the next sub-chapter. As if it were the only (pseudo-)religious item to be believed in, money is the only thing that is certain in the capitalistic reality. Kawamura claimed that because money is both a phony belief and the negative consequence of reflexive impotence (a situation in which individuals see the shortcomings of capitalism but feel powerless to change it, leading to inaction that creates a self-fulfilling prophecy and negatively impacts their mental health (Fisher, 2009)), we believe we don’t have a serious belief in it. On the other hand, we also feel as though we have no other options. He argued that if we wish to refute this, we must locate a religious artifact or alternate reality that has a greater impact on us than money. Because affect is the concept that enables us to confront such a kind of governmentality as a community action, this counter belief must be affective, a sense of certainty generated by ambiguity (uncertain certainty), and emerge collaboratively. Kawamura believed that the LoveLive! series could be that ambiguous certainty or affective-religious object.

The third sub-chapter, The Technological Condition of Anime and Affect, is no better than the second. Spanning almost five pages, Kawamura writes a great deal of mumbo jumbo in an attempt to connect the mechanism of emergence and affect with the technology of anime. In essence, anime technology facilitates emergence by generating distributive fields, which might potentially undermine the governmentality of platform capitalism. It cannot be separated from the emergence of the otaku themselves. Those who engage themselves in subcultures closely associated with anime, video games, computers, science fiction, special effects films, anime figurines, and similar media are referred to as otaku (Japanese: おたく, オタク, or ヲタク) (Azuma, 2009). According to Kawamura, otaku people emerge at the same time as the affect that makes them possible. Accordingly, in the realm of relationality, affect is the principle that allows people to transcend the pre-individual condition. Given how strongly anime inspires the feel that allows them to emerge, otaku might be thought of as a group of people who share the same affective experience. With a particular focus on the live performances of the voice actresses of the LoveLive! series, Kawamura seeks to clarify how the distributive field of LoveLive! is uniquely evocative of affect.

The fourth sub-chapter is what I had been waiting for after enduring those excruciating eleven pages of information dump. Although Kawamura still includes a significant amount of theoretical exposition and opinion, it’s a breath of fresh air that he finally applies these ideas directly to components of the LoveLive! series relevant to the discussion. He begins by linking one of the layers of anime’s distributive fields to voice acting, noting that LoveLive! has been the most successful in utilizing this element compared to its competitors. He points out that the voice actresses—mainly young women in their twenties—are very different from the characters they portray, since members of μ’s from LoveLive! and Aqours from LoveLive! Sunshine!! are high school girls. Despite this, LoveLivers genuinely enjoy and embrace the voice actresses’ live performances of their characters. According to Kawamura, this experience is enabled by the affect conveyed through the members’ voices, which communicate the voices of their characters. The experience of affect, he argues, nullifies the opposition between fiction and reality. For LoveLivers, the voice generates affect that enables them to connect the voice actresses and the characters, forming otaku individuals whose subjective views perceive an identity between the two. There is no individual with a subjective view prior to the emergence of the otaku. This is the affective reality for LoveLivers, according to Kawamura, where the line between fact and fiction is blurred, or at least relativized.

What is also interesting about this sub-chapter is Kawamura’s claim that the relationship between voice actresses and their characters is reinforced by affect. As the basis for his argument, he refers to Brian Massumi’s discussion on mirror-vision—in which an individual sees themselves as if viewed by another, creating a separation between the subject and the object—and movement-vision, where one cannot see themselves as others do while in motion, a state Massumi calls “the body without an image” (Massumi, 2002). Kawamura argues that during live concerts, the voice actresses acquire a dual identity through affect. The character “emerges” from the actresses’ bodies, and they perceive themselves as the characters in a mirror-vision of their roles. At that moment, each actress holds a dual identity: both herself and her character. The emergence of the Lovelivers elicits affect in the voice actresses on stage. The affective reality shared by Lovelivers forms a singular field that agitates the “bodies without image” of the voice actresses. Resonating with the audience’s affect, the affect of the voice actresses emerges in turn. To support his view, Kawamura cites interviews in which LoveLive! voice actresses describe their experiences of dual identity during live performances.

By the time you reach the fifth sub-chapter, it becomes apparent that reading the second and third sub-chapters was largely unnecessary, as they have little relevance to the overall conclusion. Kawamura had already introduced the foundational theories of the postsecular era, capitalist realism, and the affective-religious connection—meaning one could have skipped directly to the fourth sub-chapter without missing anything crucial. Kawamura interestingly notes that affective reality is not limited to live performances but can also be shaped through anime pilgrimage—the practice of visiting real-world locations featured in anime, games, manga, and other aspects of otaku culture (Okamoto, 2015). In the case of LoveLive! Sunshine!!, Numazu City, which serves as the anime’s setting, has become a pilgrimage site for many Lovelivers. These visits elicit emotional responses that shape a perception of Numazu as a city inhabited by the show’s characters, transforming it into an affective space. Kawamura suggests that Numazu adopts a dual identity, and through pilgrimage, fans engage with both its fictional and historical dimensions. He concludes that LoveLive! fosters a trans-individual affective crowd through its concerts and pilgrimages, effectively acting as a religious medium that connects individuals on a pre-individual level.3

First, I want to express my appreciation to Kawamura for writing this chapter and analyzing the LoveLive! series through an anthropological lens. As far as I know, there is limited literature that discusses LoveLive! as part of Japanese idol culture. However, here is my opinion: while I agree that LoveLive! functions as an affective medium, I do not believe it qualifies as a religious one. Aside from the frustrations I’ve already mentioned regarding the chapter, I feel that Kawamura’s perspective is heavily influenced by a desire to reject capitalist reality. Moreover, his argument seems more aligned with secularism rather than postsecularism, the latter of which—as Jürgen Habermas describes—acknowledges the continuing public influence and relevance of religion, even as the certainty of religion’s disappearance through modernization diminishes (Habermas, 2009). I also disagree with equating the affective with the religious. While the two may overlap in certain contexts, they are fundamentally different in meaning. Affect may indeed be a component of religious experience—for instance, religious zeal can be seen as an affective phenomenon (Tietjen, 2021)—but that does not make the two synonymous. Kawamura also overlooks the existence of LoveLivers who already hold religious beliefs before their engagement with the series. As a LoveLiver myself who also identifies as religious, I have observed that many Indonesian LoveLivers—myself included—deeply enjoy LoveLive! as an affective medium, but this does not replace or override their religious principles, contrary to what Kawamura suggests. Although my perspective may carry some bias, I believe this topic contains more nuance than Kawamura allows for and deserves a broader, more comprehensive discussion. I would like to conclude by saying that despite my disagreements and dissatisfaction with this chapter, it remains an intriguing piece of literature that I appreciate—both as a LoveLiver and as an aspiring academic.

Footnotes:

- The surname is capitalized and written first, following the full name written in kanji. ↩︎

- Yes, I’m on this picture. I’m not the one on the middle though, we were all very excited when taking this picture. ↩︎

- Wow, from 18 pages to 6 paragraphs!? Now that’s efficiency. ↩︎

References:

- Azuma, H. (2009). Otaku: Japan’s database animals. Choice Reviews Online, 46(12), 46-6967-46–6967. https://doi.org/10.5860/CHOICE.46-6967

- Fisher, M. (2009). Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? O Books.

- Habermas, J. (2009, May). A “post-secular” society – what does that mean? https://web.archive.org/web/20090329090452/http://www.resetdoc.org/EN/Habermas-Istanbul.php

- Hakuhodo Inc. (2015, May). コンテンツビジネスラボ「2015年リーチ力・支出喚起力ランキング」 |ニュースリリース|博報堂 HAKUHODO Inc. https://www.hakuhodo.co.jp/news/newsrelease/24637/

- Hiroshi, A., Galbraith, P. W., & Kovacic, M. (2021). Idology in Transcultural Perspective: Anthropological Investigations of Popular Idolatry (A. Hiroshi, P. W. Galbraith, & M. Kovacic, Eds.). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-82677-2

- Kawamura, S. (2021). Love Live! as an Affective-Religious Medium in the Postsecular Era. In P. W. and K. M. Hiroshi Aoyagi and Galbraith (Ed.), Idology in Transcultural Perspective: Anthropological Investigations of Popular Idolatry (pp. 239–258). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-82677-2_10

- Loo, E. (2010, May). Dengeki G’s, Sunrise’s Love Live Project Revealed. https://www.animenewsnetwork.com/news/2010-05-29/dengeki-g-sunrise-love-live-project-revealed

- Loo, E. (2016, May). Top-Selling Media Franchises in Japan: 2016. https://www.animenewsnetwork.com/news/2016-12-29/top-selling-media-franchises-in-japan-2016/.110442

- Love Live! | Love Live! Wikia | Fandom. (2013, May). https://love-live.fandom.com/wiki/Love_Live

- Love Live! – Wikipedia. (2021, May). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Love_Live

- Love Live! History | Love Live! Wikia | Fandom. (2015, May). https://love-live.fandom.com/wiki/Love_Live

- Massumi, B. (2002). THE BLEED: Where Body Meets Image. In Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation (pp. 46–67). Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11smvr0.6

- Okamoto, T. (2015). Otaku tourism and the anime pilgrimage phenomenon in Japan. Japan Forum, 27(1), 12–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/09555803.2014.962565

- PROJECT LoveLive! (2013a). Love Live! Official Worldwide Website | Cast & Staff. https://www.lovelive-anime.jp/otonokizaka/worldwide/caststaff.php

- PROJECT LoveLive! (2013b). Love Live! Official Worldwide Website | Story. https://www.lovelive-anime.jp/otonokizaka/worldwide/story.php

- Tietjen, R. R. (2021). Religious zeal as an affective phenomenon. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 20(1), 75–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-020-09664-4

- プロジェクトラブライブ!. (2013a). ラブライブ!Official Web Site | キャスト&スタッフ. https://www.lovelive-anime.jp/otonokizaka/caststaff.html

- プロジェクトラブライブ!. (2013b). ラブライブ!シリーズ Official Web Site. https://www.lovelive-anime.jp

- ラブライブ!シリーズ公式. (2025, April 5). ☀️#AqoursCLUB 出張所☀️ 沼津会場が本日よりOPEN🎊. https://x.com/LoveLive_staff/status/1908316154289873324