Andi Noor Faradiba Syarifin

Peace & Conflict Studies

Ankara Sosyal Bilimler Üniversitesi

In a recent webinar discussing the fatwa of jihad issued by the Forum of Islamic Ulama to Muslim countries. One speaker, representing PCINU Turki, argued that the fatwa should not be interpreted narrowly as a call to arms. Instead, he emphasized that it is a moral proposition, an appeal from religious scholars to governments, and its implementation or obligation depends on the interpretation and endorsement of each state’s ruling authority.

While this perspective offers a careful legalistic framing, a deeper issue emerged in his discourse that raised a concern: a troubling detachment from moral and empirical realities. The speaker refused to use terms like occupation, colonization, or Zionist extemist when discussing the situation in Palestine, insisting that such labels were beyond his expertise or capacity. At one point, he even explained how the Israeli government allows religious freedoms, an observation that, while technically accurate on paper, flattens the profound daily violations occurring on the ground.

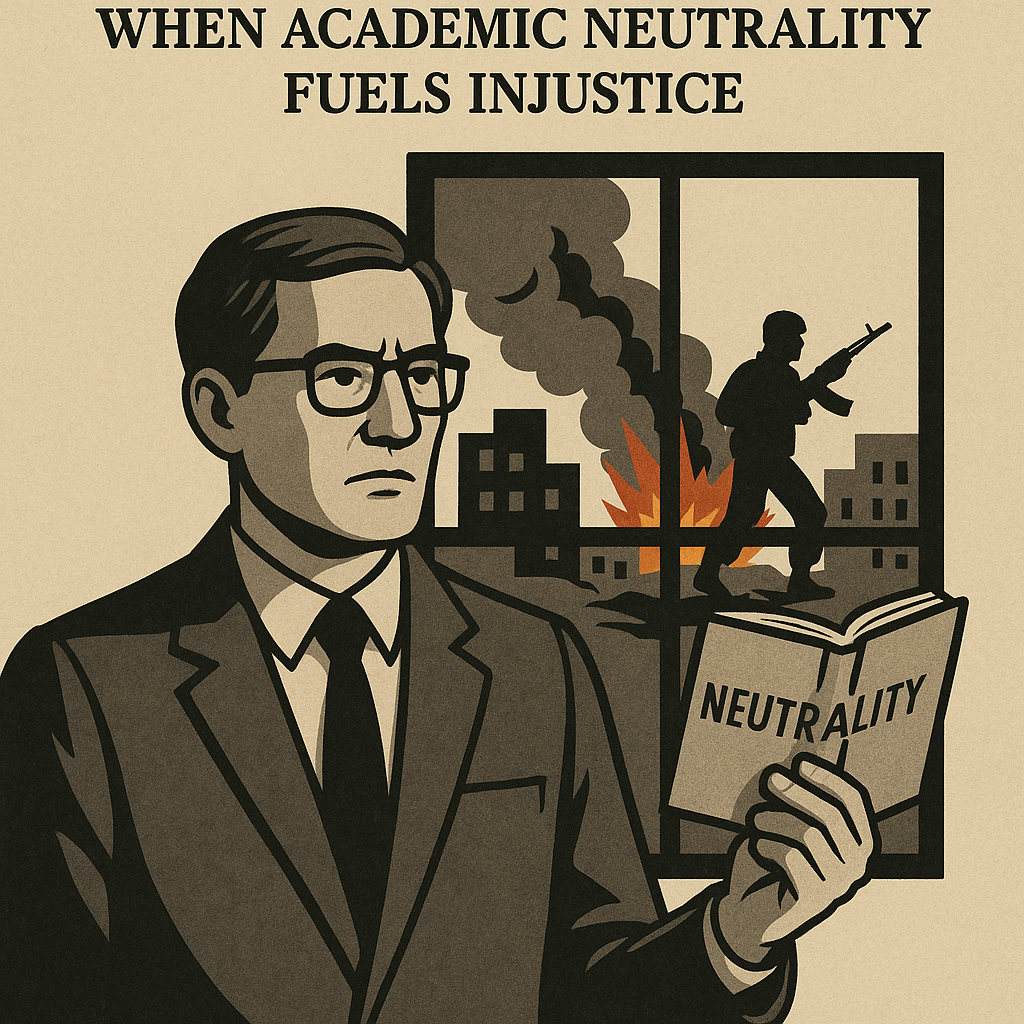

This detachment reflects a larger issue: the growing tendency among scholars, analysts, and public intellectuals to shelter behind institutional neutrality or disciplinary boundaries while real-world atrocities unfold before us. It is an easy way out to treat written laws, statements, and treaties as sufficient representations of reality. Our task as scholars is not just to quote, categorize, or remain cautiously noncommittal; it is to interrogate the gap between what is written and what is lived.

The Ethical Pitfalls of “Neutrality”

In journalism and academia alike, the principle of objectivity is frequently misunderstood as neutrality, even in the face of overwhelming evidence of injustice. But neutrality, in many contexts, becomes a veil for complicity. As the Ethical Journalism Network (2023) warns, false balance reporting in conflict zones can obscure actual power asymmetries and lead to ethical failure, just as it did during the Rwandan genocide.

Similarly, Al Jazeera Media Institute (2024) critiques how Western journalism, in the name of balance, marginalizes Palestinian narratives while reinforcing dominant state-centric discourse. By prioritizing formal symmetry over lived truth, journalists may fail upward, appearing balanced while contributing to mass ignorance and injustice.

A journalist Mehdi Hasan famously said: “If A says it’s raining and B says it’s dry, your job as a journalist isn’t to quote both and call it a day. Your job is to open the f**ing window & find out if it’s raining.” Scholars, like journalists, must be willing to look, honestly, directly, and unflinchingly through their windows.

Academic Detachment and Complicity

At one point in the webinar, the speaker shared how someone in his institution once asked both Israelis and Palestinians: “Why can’t you just sit and talk?” On the surface, this sounds reasonable. But in reality, such a question, posed without full understanding of the power imbalance, can come across as deeply dismissive. It belittles the intelligence and lived experiences of those who have endured decades of violence, betrayal, and broken agreements.

No population jumps into armed conflict without years of failed negotiations, violated accords, and unbearable oppression. To ask why they can’t just talk is to ignore the fundamental truth: peace talks are impossible if one side is treated as inherently inferior, and the other is armed with the most modern weapons of war.

As Ghassan Kanafani said when asked why not talk with Israeli leaders, “ It is a conversation between the sword and the neck” (@jvplive, 2021). And until that imbalance is addressed, every call for dialogue that ignores context only reinforces the very structures that perpetuate violence.

The problem is not limited to journalists. Academia has long grappled with its own version of detachment. Scholars like Dadabhoy and Rambaran-Olm (2024) have argued that academic freedom should empower scholars to speak out against injustice, not silence them. Yet across Western universities, pro-Palestinian scholars and students increasingly face censorship, intimidation, or disciplinary action for naming what is plainly visible: a genocide unfolding in real time.

The Transnational Institute (2024) describes how academic institutions risk complicity when they maintain partnerships with entities linked to oppressive regimes or suppress faculty dissent to preserve reputational capital. Neutrality becomes not just passive, it becomes strategic silence.

Even within genocide studies, there is hesitation. As The Guardian reported, many scholars have been reluctant to describe events in Gaza as genocide due to political sensitivities, despite legal experts like Raz Segal asserting that the threshold is not only met but exceeded (Beaumont, 2024).

An article from TRT World (2024) further highlights how academic neutrality has become a plague on scholarly discourse. It shows how truth is being sacrificed in elite academic circles under the pressure to avoid confrontation or backlash, turning campuses into spaces of silence rather than moral leadership.

It is not only Western institutions. Many Arab universities and institutions have also suppressed or avoided firm public positions in fear of diplomatic repercussions. Meanwhile, in Indonesia, while universities and institutions are not under the same degree of scrutiny or censorship, they too often adopt a passive, non-aggressive narrative under the guise of neutrality and mediation. But neutrality, when weaponized as avoidance, is not a virtue. It delays justice.

The responsibility to speak truth is not waived by geography or strategic diplomacy. The goal of peace and reconciliation must begin with the truth. The liberation of Palestine is inseparable from the liberation of Israelis themselves, both parties are ensnared in a system of violence and denial that must be dismantled. And that dismantling begins by acknowledging injustice. We cannot claim to seek resolution without first addressing root causes.

As scholars, we cannot contribute to liberation if we are too busy defending our own privilege and comfort zones.

The Fallacy of “Not My Expertise”

It is deeply irresponsible of us to take the easy way out of a discussion with the excuse of being impartial or removing ourselves from empathy, believing that it somehow expresses our expert objectivity. But expertise without empathy is not wisdom. The knowledge we acquire, through study, research, or lived experience, should make us more human, not more detached. If the knowledge we pursue doesn’t lead us to empathy first, then what good is it?

When faced with moral crises, many scholars retreat into disciplinary modesty: “I’m not a political scientist,” “I’m not an international lawyer.” But truth-seeking is not a siloed endeavor. In the face of atrocity, this kind of academic compartmentalization becomes an abdication of responsibility.

The division of academic labor should not be a division of moral accountability. If our disciplines become excuses to avoid speaking out, we are not merely silent, we are shielding injustice under the banner of expertise. Detachment becomes dangerous not because it is neutral, but because it allows impunity to flourish under the illusion of professional restraint.

The Moral Imperative to Engage

This is why disciplinary modesty is not enough. The frequently used disclaimer, “this isn’t my field”, becomes a shield against accountability. But truth-seeking is not limited by departmental boundaries. You do not need to be an international lawyer to recognize apartheid. And you do not need to be a historian of the Holocaust to understand that ethnic cleansing, starvation, collective punishment, and military sieges constitute crimes against humanity.

As one participant in the webinar noted, none of us were alive during the Holocaust, yet we all universally condemn it. So why, when genocide is unfolding during our lifetime, digitally documented, legally analyzed, and morally visible, do so many hesitate to speak clearly? Why do we defer to euphemism and institutional caution?

Our generation faces an unprecedented ethical test: to name what we are witnessing with moral clarity, and to act upon it with responsibility.

The Responsibility of Our Time

Today, the greatest responsibility in defining complicity lies with us, not future generations. It is not the responsibility of those who will come after us to see clearly and condemn unequivocally this genocide, just as we now do when speaking about the Holocaust. That duty, that clarity, must come from us, here and now.

If we remain silent, if we retreat behind neutrality and non-expertise, we are not impartial observers, we are enablers. The truth is, no ideology, no discourse war, no sacred book or theory, however revered, can outweigh the tangible, systematic destruction of a people. What is happening to Palestinians is not abstract. It is not theoretical. It is lived, documented, visible, and daily.

It is always easier to analyze conflict in black and white from our safe moral high ground, when it is not our necks on the gallows. But the privilege of distance does not excuse intellectual cowardice. And if we limit our understanding to what our institutions dictate, we are not truth-seekers. We are institutional parrots.

References

- @jvplive. (2021, July 8). It is a conversation between the sword and the neck. [Video]. X. https://x.com/jvplive/status/1413171509330255873

- Al Jazeera Media Institute. (2024). Revisioning journalism during genocide. https://institute.aljazeera.net/en/ajr/article/revisioning-journalism-during-genocide

- Beaumont, P. (2024, December 20). Genocide definition divides scholars over Gaza. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/dec/20/genocide-definition-mass-violence-scholars-gaza

- Dadabhoy, A., & Rambaran-Olm, M. (2024, January 20). Scholars should be able to speak out against genocide without fear. Truthout. https://truthout.org/articles/scholars-should-be-able-to-speak-out-against-genocide-without-fear-of-punishment

- Ethical Journalism Network. (2023). Ethical choices when journalists go to war: Introduction. https://ethicaljournalismnetwork.org/ethical-choices-when-journalists-go-to-war-introduction

- @mehdirhasan. (2020, July 27). Your job is to open the f**ing window & find out if it’s raining. [Post]. X.

- Transnational Institute. (2024). The circus of academic complicity. https://www.tni.org/en/article/the-circus-of-academic-complicity

- TRT World. (2024). Truth sacrificed as academic neutrality on Gaza plagues scholarly discourse. https://www.trtworld.com/opinion/truth-sacrificed-as-academic-neutrality-on-gaza-plagues-scholarly-discourse-16857361